CAVEON SECURITY INSIGHTS BLOG

The World's Only Test Security Blog

Pull up a chair among Caveon's experts in psychometrics, psychology, data science, test security, law, education, and oh-so-many other fields and join in the conversation about all things test security.

Can Good Items Have Bad Item Statistics? DOMC™ Findings

Posted by Sarah Toton, Ph.D.

updated over a week ago

Good Items Can Have Bad Item Statistics

Every psychometrician knows that tests can be improved by removing misbehaving items. Items that are too hard, too easy, or don’t correlate well with the rest of the test items or the overall score are often flagged for revision or removal from a test. But what if that isn’t the full story? In this article, I hope to provide you with evidence that good items can have bad item statistics.

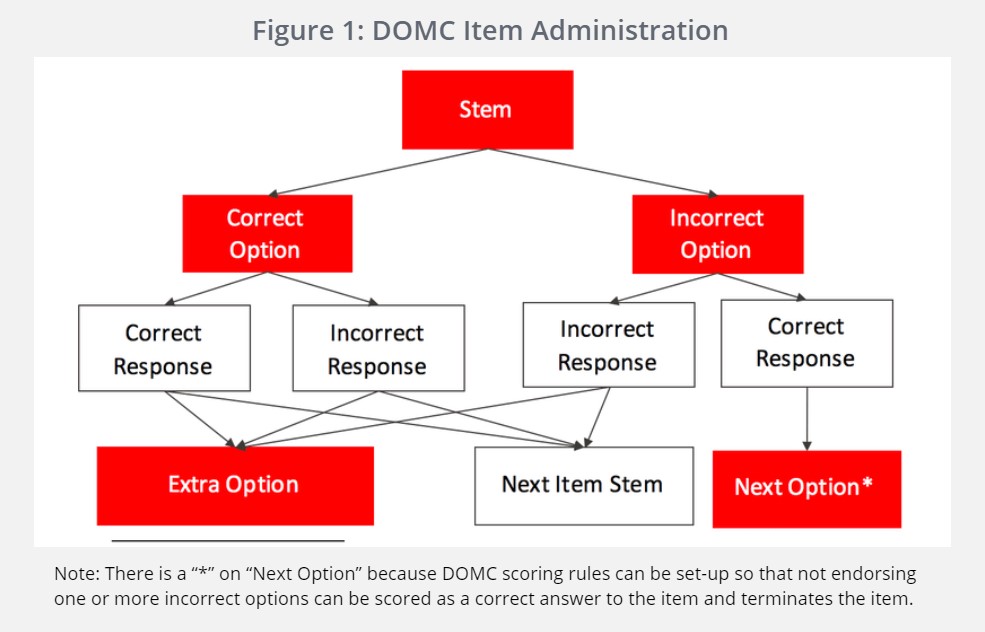

The item I will present was administered as both a multiple-choice item and a Discrete Option Multiple Choice™ (DOMC) item, with similar results. We will discuss the DOMC item version in this article. (For an overview of how DOMC items work, see Figure 1 below, or read the white paper here.)

DOMC™ Items

In a DOMC item, the item stem is presented and then options are presented one at a time (in a randomized order). Using standard DOMC scoring, an item terminates when 1) the correct option is endorsed* as correct (item score of 1), 2) the correct option is not endorsed (item score of 0), or 3) an incorrect option is endorsed as correct (item score of 0). After the item terminates, one of the options may be given as an extra, unscored option with some pre-determined probability (e.g., .40 for example indicates that 40% of the time, an extra option is given when the item terminates) for security purposes (to avoid disclosing the correct answer to the item). Then, the test moves on to the next item.

[*] The term “endorsed” means the test taker indicated that the option was correct. Conversely, “not endorsed” means that the test taker indicated the option was not correct.

The Example: A Harry Potter DOMC Item

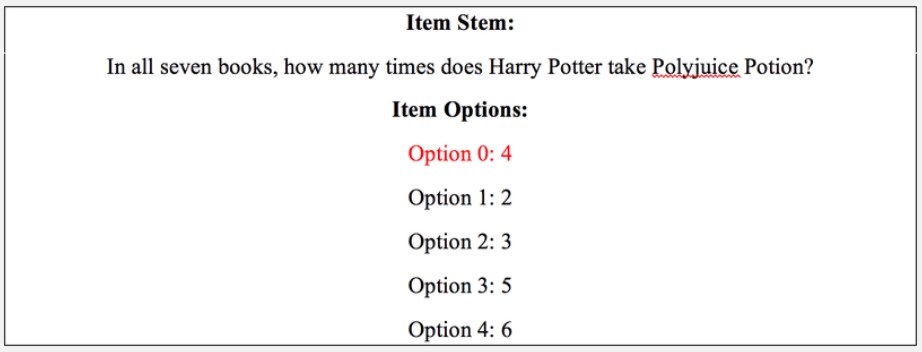

The specific item I will discuss, below, is from a test measuring knowledge of Harry Potter trivia:

The correct answer to this item is 4 (Option 0). For Harry Potter fans, those times are 1) when Ron and Harry transform into Crabbe and Goyle look-a-likes to interrogate Malfoy in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, 2) when Harry, Ron, and Hermione impersonate employees of the Ministry of Magic, 3) when Harry and Hermione impersonate muggles to visit Godric’s Hollow, and 4) when Harry impersonates a muggle boy to attend Bill and Fleur’s wedding (all of these instances except the first are in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows).

The Item Statistics

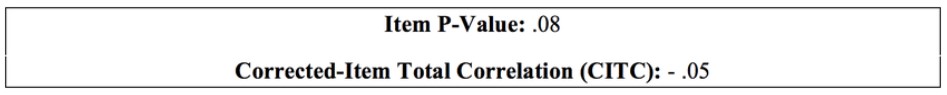

The item statistics for this item are given below:

These findings show that 8% of examinees get this item correct (p-value) and if an examinee responds to this item correctly, that does not indicate much about their scores on the remainder of the items (CITC is very weak/close to zero and slightly negative). These item statistics would usually be interpreted as indicative of poor item functioning.

The Endorsement Rates

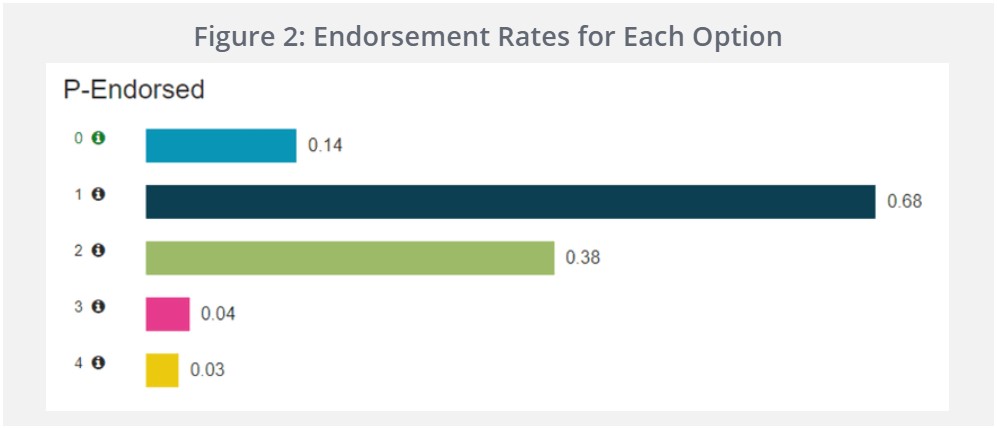

However, when we look at the percentage of times that each option is endorsed as correct when it is presented, we see some interesting things happening in this item’s options (See Figure 2, below). Two of the distractors (Options 3 and 4) were very rarely endorsed (3% and 4%). The correct answer (Option 0) was endorsed about 14% of the time. The remaining two distractors (Options 1 and 2) were endorsed 68% and 38% of the time.*

[*] Note that these amounts do not add up to 100% because for each option we are calculating the number of people who endorsed that option divided by the number of people who saw that option. Examinees can see multiple options, contributing to the denominator for multiple options, but can only endorse one for this Harry Potter test, ignoring the random extra option.

This indicates that of the five options, two are very easy distractors that don’t really contribute meaningful information to the item, two are very hard distractors that examinees often select, and the remaining one is the correct answer. In this item, an incorrect option is the most likely to be endorsed.

What exactly is happening with Option 1? How can an incorrect option be so frequently endorsed? Option 1 states that Harry took Polyjuice Potion two times across all seven books. Upon extensive review of the Harry Potter books and movies (for research, of course!), I noticed that Harry only takes Polyjuice Potion twice in the movies (to impersonate Goyle and to impersonate Albert Runcorn, a Ministry of Magic employee). In fact, sometimes the books and movies are in direct conflict with each other, with one stating Harry used Polyjuice Potion and the other stating he didn’t. For example, during the Godric’s Hollow scene in the movies, Harry strongly defends NOT using Polyjuice Potion, even though he used it in the books. Below is that exact conversation from the movie:

Even if an examinee who is responding to this item thinks Harry might have taken Polyjuice Potion in Godric’s Hollow, they might disregard that instance because of the strong statement during this scene in the movie.

So where does that leave us? An examinee who is deeply familiar with the books, but not the movies, will probably select 4 (Option 0), the correct option. An examinee who is deeply familiar with the movies, but not the books, will likely select 2 (Option 1), an incorrect option. An examinee who is familiar with both the books and the movies, as we expect self-proclaimed Harry Potter experts to be, may select "2" (drawing primarily on movie knowledge), "3" (drawing on book knowledge but disregarding the Godric’s Hollow instance because of the strong statement in the movies), or "4" (drawing primarily on book knowledge).

Thus, this item appears to show these patterns because of two very powerful, but incorrect, distractors. The power of these two incorrect distractors is driven by the differences between the books and the movies. So now we know that this is a very difficult item that doesn’t relate well with the other items and we have some ideas about why, but is the item worth keeping?

The Person-Item Map

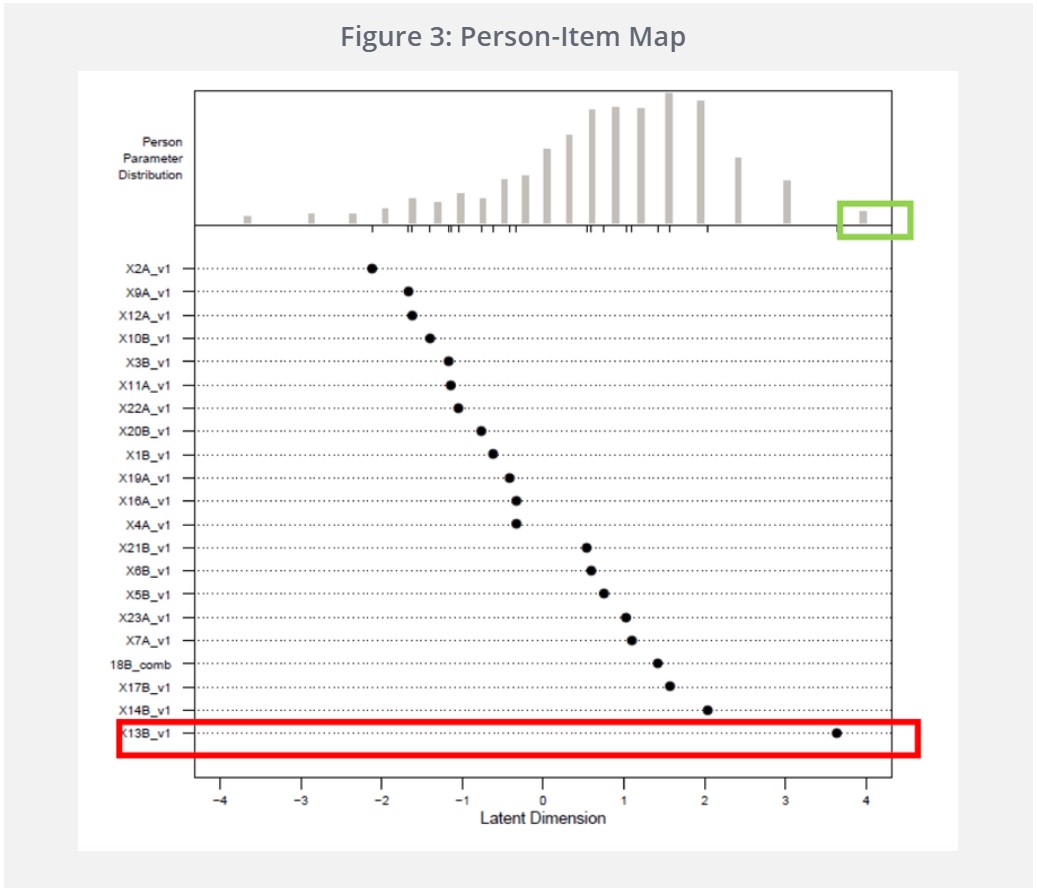

Figure 3, below, is a person-item map. Item difficulty and person ability are estimated on the same scale (computed with the Rasch model) and plotted together. Both item difficulty and person ability are presented with low estimates on the left and high estimates on the right. At the top of the figure is the distribution of all of the examinees’ estimated ability levels and underneath are dots representing the item difficulty estimates.

Ideally, a person-item map shows good correspondence between the item difficulties and the person ability levels. That seems to be the case here as most areas of the person ability distribution have items of appropriate (matching) difficulty. The box in green indicates the high-performing examinees and the box in red indicates the item in question. The data in this figure shows that this item, although very difficult, is appropriately difficult for the high-performing examinees in this sample.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this example item on Harry Potter trivia shows that even items with “bad” statistics may be appropriate, and they may not necessarily require revision or removal. The cons of keeping such an item are that it could reduce the consistency of a scale, loading poorly on the construct of interest in factor analyses and/or lowering the reliability (in this case, by less than .01). However, in the current case, the evidence indicates that the item is providing useful information, especially when administered to high-ability examinees.

Sarah Toton, Ph.D.

Dr. Sarah Toton is a Psychometrician and Data Forensics Scientist at Caveon where she conducts analyses for a broad range of clients. She received a Ph.D. in Quantitative Psychology from the University of Virginia, and an MA in Psychology from Wake Forest University. Her current research focuses on identifying predictors of item compromise and examinee pre-knowledge, particularly those that are based on item response time statistics. A winner of the Benjamin D. Wright Innovations in Measurement Award, she brings a strong background in Item Response Theory to her work and a creative approach to the challenges of an area with many unknown factors. Sarah regularly presents her work at The Conference of Test Security and is a member of the National Council of Measurement in Education.

View all articlesAbout Caveon

For more than 18 years, Caveon Test Security has driven the discussion and practice of exam security in the testing industry. Today, as the recognized leader in the field, we have expanded our offerings to encompass innovative solutions and technologies that provide comprehensive protection: Solutions designed to detect, deter, and even prevent test fraud.

Topics from this blog: Exam Development DOMC™

Posts by Topic

- Test Security Basics (34)

- Detection Measures (29)

- K-12 Education (27)

- Online Exams (21)

- Test Security Plan (21)

- Higher Education (20)

- Prevention Measures (20)

- Test Security Consulting (20)

- Certification (19)

- Exam Development (19)

- Deterrence Measures (15)

- Medical Licensure (15)

- Web Monitoring (12)

- DOMC™ (11)

- Data Forensics (11)

- Investigating Security Incidents (11)

- Test Security Stories (9)

- Security Incident Response Plan (8)

- Monitoring Test Administration (7)

- SmartItem™ (7)

- Automated Item Generation (AIG) (6)

- Braindumps (6)

- Proctoring (4)

- DMCA Letters (2)

Recent Posts

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Get expert knowledge delivered straight to your inbox, including exclusive access to industry publications and Caveon's subscriber-only resource, The Lockbox.