CAVEON SECURITY INSIGHTS BLOG

The World's Only Test Security Blog

Pull up a chair among Caveon's experts in psychometrics, psychology, data science, test security, law, education, and oh-so-many other fields and join in the conversation about all things test security.

Goodbye, Multiple Choice

Posted by David Foster, Ph.D.

updated over a week ago

Table of Contents

- The Beginnings of Multiple Choice

- History of the Multiple-Choice Item

- Multiple-Choice Items vs. Selected-Response Formats

- The Concretization of Multiple Choice

- The Faults of Multiple Choice

- A Section Dedicated to Honoring Multiple Choice

- Alternatives to Multiple-Choice Items

- The multiple-correct multiple-choice question

- The Discrete Option Multiple Choice question

- Randomizing the content for a selected-response question

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

The Beginnings of Multiple Choice

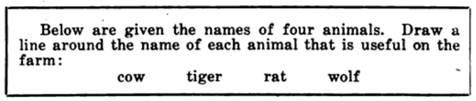

The title of this article refers not to a human friend, but to my long-time assessment companion, the venerable multiple-choice question. Invented by Frederick Kelly in 1915, the multiple-choice item type first appeared in the Kansas Silent Reading Test. An example of an item from this test is shown in Figure 1. Bubble answer sheets were not invented at that time, so the student was simply instructed to draw a line around the correct answer.

Figure 1. Example multiple-choice item from the Kansas Silent Reading Test, used in the test’s instructions.

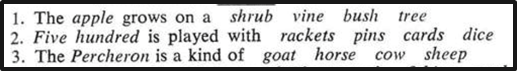

Only a couple of years later, in 1917, the multiple-choice item made a significant contribution to the World War I war effort when it appeared on the U. S. Army Alpha and Beta tests, which were used to quickly classify recruits for service. Figure 2 shows the first three questions of the Army Alpha, all multiple choice. These are from Test 8, one of the test forms taken by recruits. Test takers were instructed to simply underline the correct answer.

Figure 2. Multiple-choice items from the Army Alpha test.

From these beginnings, the simple multiple-choice question quickly became the foundation of modern testing. Since then, common characteristics of nearly all multiple-choice questions have included several options for each question, usually four, and only one of those options being correct. (Of course, there have been occasional variations in the number of options and the number of correct answers.) Compared to other early methods of testing, the advantages of the multiple-choice item were monumental: clear measurement, efficient test administration, and unbiased scoring.

The Multiple-Choice Item as One Variety of the Selected-Response Format

It’s very important not to equate the multiple-choice item type with selected-response items. Selected-response questions are a broader category where the questions and its parts are created in advance, presented during the test, and where the test taker simply responds by selecting a response rather than constructing a response. The traditional multiple-choice question is just one type of selected-response question. There are many other forms of selected-response questions that should be considered by testing programs as excellent replacements for multiple choice. More on that later.

The first couple of decades of the 20th century also saw many other important inventions. Examples include the automobile, powered flight, and the telephone. We are all familiar with how each of these have adapted and flourished. Today’s cars look and perform nothing like the Model T Ford. Progress in powered flight has taken us from propellers to jet engines to rocket boosters. We have even sent vehicles to space. Similarly, the telephone has changed in hundreds of ways since the turn of the 20th century, resulting in your smartphone, a sophisticated computer that enables direct communications, social media, and information transfer on a scale undreamed of 100 years earlier.

In stark contrast to these examples, the multiple-choice question has remained static, appearing and used today in exactly the same way as it was 100 years ago. Of course, there are alternatives (many of which are excellent item types), but the original version remains the mainstay of assessments everywhere. It has a committed group of users, and every test administration system, test development system, and statistical analysis tool over the past ten decades have been built to prioritize multiple choice. Yet, despite the fact that critics inside and outside of the testing industry correctly point out its faults, the majority of individuals staunchly defend it and are reluctant to consider alternatives.

The Concretization of Multiple Choice

There is no doubt that the multiple-choice question is an institution. It has been institutionalized in the true sense of the word. This explains why it has endured for more than a century without being replaced by something better, why it is immune to criticism, and why it hasn’t gone through transformations as we have seen with flight, cars, and phones. The institutionalization of the multiple-choice question actually says more about the testing industry than it does the question format. Our industry decided decades ago to turn it into a “gold standard” of testing.

I admit that in my 30+ years, I contributed to this institutionalization. I learned the proper rules to write such questions and train others, how to give them to test takers, how to collect the proper data, and how to statistically analyze them. I learned how to defend multiple choice to critics. I was thrilled to be able to work with such a simple and magnificent tool. I even built software systems to make using multiple-choice questions easier. Essentially, I’ve made a career on being good at multiple-choice-question-based testing. It is only recently that I have come to understand the failings of multiple choice, particularly from a security standpoint, and realized that it’s time for multiple choice to be replaced with better item formats.

The Faults of Multiple Choice

At this point, some reading this may be poised to defend multiple choice once again—as I have done many times in the past. You might wonder what is wrong with it or whether its flaws are really so bad. After all, in many ways, it is easier for all concerned to keep it as it is rather than confronting the difficulty of replacing it.

But the multiple-choice item does have major flaws that we can’t continue to ignore. Here are five of the most pertinent:

- The multiple-choice question is unfair. It allows and even encourages the use of testwiseness. Testwiseness is when a test taker uses test-taking strategies to achieve a better score. Testwiseness is irrelevant to what an exam is actually trying to measure, and it allows one test taker to unfairly gain a significant advantage over another. This disadvantage generalizes to groups of test takers defined by age, race, gender, culture, country, and more. This failing alone makes the multiple-choice question type unfit for use, especially when alternatives exist.

- The multiple-choice question is a security risk. It is easy to “harvest” test items by memorization, cell phone cameras, voice recordings, etc., and then share them on the internet or with friends or colleagues. Because the item displays all of the options simultaneously and the stem never changes, individuals who can acquire or purchase exposed test questions are able to effectively cheat using pre-knowledge. Pre-knowledge is a common, easy-to-do, and low-risk way to cheat—and it endangers ALL testing programs that rely on multiple-choice items.

- The multiple-choice question causes confusion. By design, multiple choice causes test-taking errors. For example, to maintain its “single-correct” format, testing programs routinely negatively word their stems. (“Which is NOT a real number?”) This confuses test takers, particularly those with divergent language or reading abilities. As another example, multiple-choice writers are instructed to create “distractors.” These are deliberately designed to be attractive, tempting, and incorrect. It’s these types of options that give rise to the valid criticism that multiple-choice questions are unnecessarily “tricky.”

- The multiple-choice question is misunderstood. Many testing programs, item writers, and testing critics equate “simple multiple choice” with the measuring “simple skills” (usually the recall of knowledge)[1]. This has encouraged simplistic measurement and simplistic tests. I disagree energetically with the notion that the multiple-choice question can only be used to measure simple skills. But I agree that that is the way it is viewed by the public and used by many testing programs. The reality is that multiple choice has always been capable of much more.

The multiple-choice question discourages progress. Even with the widespread use of computers to create and administer tests, the multiple-choice question is built, administered, and scored exactly[2] as it was in 1915. I get pensive about how testing might have evolved today and how much greater of an impact it might have had on society if it had been free to adapt.

These are just a few of the more pertinent problems with the multiple-choice item type. You can read more about the multiple-choice item type in this white paper. With these points in mind, it is clear that the multiple-choice item represents a threat to validity, reliability, security, and fairness. My hope is that by acknowledging these problems, we can either fix the multiple-choice question or move on to embrace new and more effective item types.

Honoring Multiple Choice

We should not replace the multiple-choice question without giving it its due. We need to praise what it has accomplished. It quite literally provided information that saved lives in World War I. Over the decades since, it has worked its magic in assessing the achievements of school children, the likelihood of success in college, the suitability for a job, and many other vital purposes.

Having no other options (excuse the pun) for most of that time, we relied on multiple choice exclusively. And it came through for us. It was fairly straightforward to write and quick to score. So, as a tribute to its long-standing value (but not without significant risk), we continue to use it today for almost every high-stakes exam.

Alternatives to Multiple Choice

Better options now exist that can effectively replace the multiple-choice item. There are plenty of technology-based replacements to the traditional multiple-choice question now available that effectively address the flaws of the multiple-choice question. Here are three easy-to-use selected-response alternatives that all programs can begin using immediately:

Alternative 1: The Multiple-Correct Multiple-Choice Question

At Novell in 1990, my team began writing multiple-choice questions with more than one correct answer so we could eliminate negatively worded stems and remove at least a small source of error and confusion. We found that our certification candidates, most of whom were non-native-English speakers and/or from non-U.S. cultures, made errors when trying to understand the backward negative wording. The problem was exacerbated when the items were translated into other languages. Figure 3 shows the traditional item alongside the simpler, improved version.

Figure 3. Comparison of a negatively worded multiple-choice question with a less confusing alternative. For the question on the left, only one response is allowed, while three are required for the one on the right.

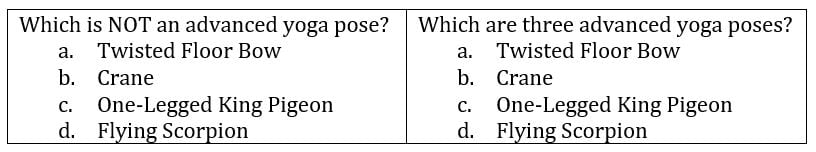

Alternative 2: The Discrete Option Multiple Choice Question

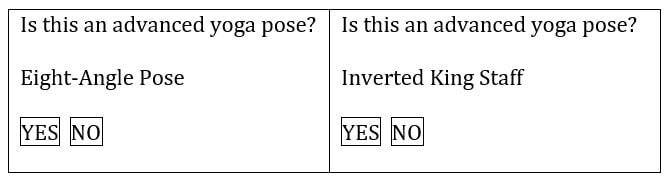

Another innovative selected-response variety, one that preserves the spirit of the traditional multiple-choice question, is the Discrete Option Multiple Choice™ (DOMC) item type. The DOMC™ question specifically harnesses new computing technology to remove unfairness due to testwiseness, reduce security risks, and save time and development costs. The DOMC question presents options one at a time instead of simultaneously. The question requires a “Yes” response if the person believes the option to be correct, and a “No” if they think it is incorrect. The question keeps presenting options until it has been answered either correctly or incorrectly. Figure 4 illustrates two consecutive options from a DOMC question using the same “yoga poses” content as before.

Figure 4. Two possible options for a DOMC question on advanced yoga poses. The second and following options may appear depending on how the test taker answers earlier ones.

The DOMC question solves many of the faults of the multiple-choice question. I will describe two here:

-

- By not presenting options simultaneously, most test-taking skills (including testwiseness) cannot be used. Presenting the answer options individually reduces a significant source of unfairness.

- The DOMC question can support more than four or five options. As a result, DOMC questions can be written with hundreds of options in a pool of options. Of those, only two to three options might be exposed to each test taker. This reduction in exposure makes it difficult for individuals to harvest the question content, share it online, or allow others to cheat using pre-knowledge. This serves to increase the overall fairness and validity of exams.

- By not presenting options simultaneously, most test-taking skills (including testwiseness) cannot be used. Presenting the answer options individually reduces a significant source of unfairness.

Alternative 3. Randomizing the Content for a Selected-Response Question.

In the middle of the 20th century, highly-respected testing professionals Frederick Lord, Lee Cronbach, and Jason Millman, among others, promoted the idea of a Randomly Parallel Test (RPT)—you can learn more about their findings in this article. In short, an RPT presents a unique test for each test taker. The test is created by selecting items at random from a very large pool that represents a domain of content. This interesting test design was supported by test theory and statistical procedures. These testing scions viewed RPT as the ideal method of testing, but they knew it was not feasible given their limited technology. Today, however, RPTs are not just feasible, but they are being used on operational tests.

Traditional multiple-choice questions are characterized by fixed content. The content and questions on a test never change (even if there are multiple forms). But with the RPT, the content of the questions is designed to change from one test taker to the next.

Recently, Caveon introduced the SmartItem. When used on a test, the SmartItem converts the test from static content to an RPT. The SmartItem selects content randomly from a domain on the fly during a test and presents a unique rendering of each SmartItem to every test taker. Such an item design makes it almost impossible to benefit from item theft or cheating on tests, while at the same time measuring a person’s competence on every domain the test covers.

Conclusion

I don’t expect these new varieties, or others that have been introduced in the past couple of decades, to be the end game result. In fact, I hope that all of these alternatives evolve over the next 100 years to continue to fit the ever-changing needs of society. But to get there, the first step to this grand vision is to say a fond (but long overdue) farewell to our old friend: the multiple-choice question.

Footnotes

[1] My initial objection to the characterization of simplicity is that “recall of information” is not a simple thing, as every good psychologist and every average human being who has forgotten something can attest. But it is treated, almost dismissed, as a “simple skill” by most professional testing experts, the public, and by testing critics.

[2] By “exactly,” I’m momentarily ignoring some good innovations in the multiple-choice question format and how it might be scored, and referring to its overwhelming dominance of use in virtually all testing that takes place worldwide.

David Foster, Ph.D.

A psychologist and psychometrician, David has spent 37 years in the measurement industry. During the past decade, amid rising concerns about fairness in testing, David has focused on changing the design of items and tests to eliminate the debilitating consequences of cheating and testwiseness. He graduated from Brigham Young University in 1977 with a Ph.D. in Experimental Psychology, and completed a Biopsychology post-doctoral fellowship at Florida State University. In 2003, David co-founded the industry’s first test security company, Caveon. Under David’s guidance, Caveon has created new security tools, analyses, and services to protect its clients’ exams. He has served on numerous boards and committees, including ATP, ANSI, and ITC. David also founded the Performance Testing Council in order to raise awareness of the principles required for quality skill measurement. He has authored numerous articles for industry publications and journals, and has presented extensively at industry conferences.

View all articlesAbout Caveon

For more than 18 years, Caveon Test Security has driven the discussion and practice of exam security in the testing industry. Today, as the recognized leader in the field, we have expanded our offerings to encompass innovative solutions and technologies that provide comprehensive protection: Solutions designed to detect, deter, and even prevent test fraud.

Posts by Topic

- Test Security Basics (34)

- Detection Measures (29)

- K-12 Education (27)

- Online Exams (21)

- Test Security Plan (21)

- Higher Education (20)

- Prevention Measures (20)

- Test Security Consulting (20)

- Certification (19)

- Exam Development (19)

- Deterrence Measures (15)

- Medical Licensure (15)

- Web Monitoring (12)

- DOMC™ (11)

- Data Forensics (11)

- Investigating Security Incidents (11)

- Test Security Stories (9)

- Security Incident Response Plan (8)

- Monitoring Test Administration (7)

- SmartItem™ (7)

- Automated Item Generation (AIG) (6)

- Braindumps (6)

- Proctoring (4)

- DMCA Letters (2)

Recent Posts

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Get expert knowledge delivered straight to your inbox, including exclusive access to industry publications and Caveon's subscriber-only resource, The Lockbox.